A Case of Mistaken Identity

with Mick Oates

From "52 More Things You Should Know About Palaeontology" edited by Alex Cullum and Allard Martinius, Agile Libre Publications, 2017.

From the dawn of civilization, humans have been picking up fossils and pondering what they could possibly mean. Up until the Age of Reason (mid-seventeenth to mid-eighteenth century) very few considered that fossils could ever have been alive. And why should they? There was no concept of geological time, and how could an animal have been turned to stone, except perhaps by an encounter with a Gorgon? Fossils were variously described as "sports of nature", products of a "plastic virtue latent in the earth", or unsuccessful attempts by life to emerge from the rock by spontaneous generation. The Danish anatomist Nicholas Steno was one of the first to recognize that fossils had once been living creatures, when in 1666 he connected curios known as "tongue stones" with modern-day sharks' teeth.

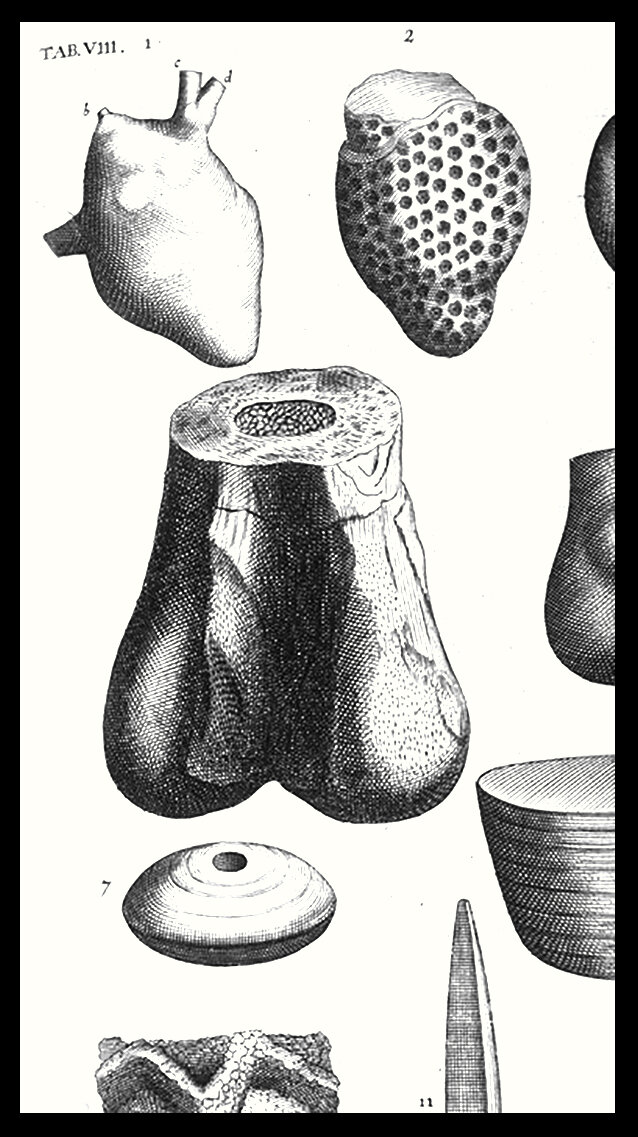

The realization that fossils were ancient life forms brought a slew of misidentifications which, although hilarious today, were perfectly understandable at the time. The organic and inorganic were routinely confused, so innocent concretions became "stone hearts", "bulls' heads" and "flint feet", while belemnite guards were thought to be "thunderbolts". And, notoriously, one of the earliest dinosaur bones was mistaken for a pair of testicles. If you look at the illustration, it's easy to see why. The fossil, actually part of the femur of the predatory Megalosaurus, was first described by Robert Plot in his Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677). Plot speculated that the bone came from a race of giants that once populated the Earth, but the physician Richard Brookes clearly had a very specific part of the anatomy in mind when, in 1766, he reclassified the specimen as Scrotum humanum. Lest we chortle too much, let's not forget that it would be another 60 years before the first dinosaur – fittingly, Megalosaurus - was described by William Buckland.

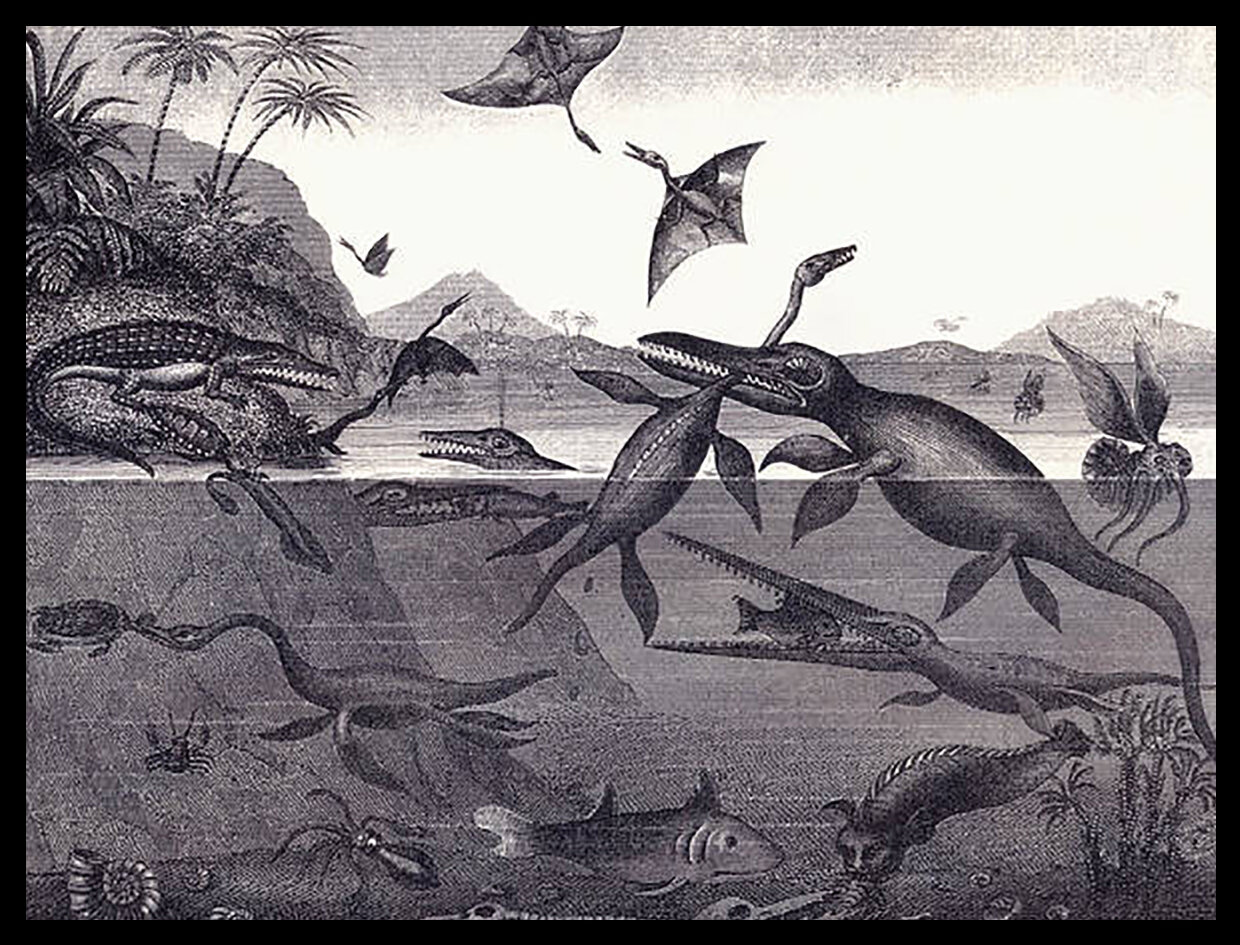

In those days, it was pretty easy to make mistakes about function too. Henry de la Beche's famous drawing Ancient Dorsetshire (1830) – rightfully celebrated as one of the first attempts to envisage a palaeoenvironment – shows ammonites sailing serenely on the surface like Spanish galleons amongst the general Jurassic carnage. The notion seems to have persisted in William Evans, Lord Energlyn's Through the Crust of the Earth (1973), which has the recumbent bivalve Gryphaea riding the ocean wave like a boat, while ammonites become "ancient submarines". A regular Jurassic flotilla…..

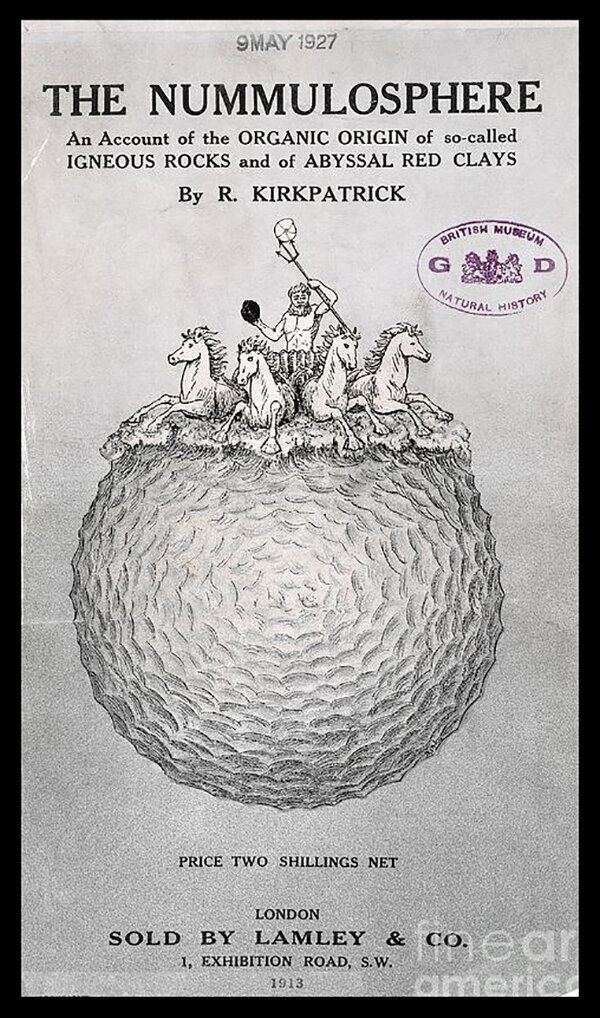

It's also perfectly possible to perceive signs of life based on no evidence whatsoever. We've all done it at some time or other. Stare at a page of random dots for long enough, and eventually you start seeing complex shapes. This human need to discern patterns in meaningless information has even got a name: apophenia. Its greatest geological exponent was Randolph Kirkpatrick (1863-1950), an assistant keeper at the British Natural History Museum. Kirkpatrick became obsessed with the large foraminifera called nummulites, and started seeing their characteristic concentric patterns everywhere, including in igneous rocks. Full-blown monomania took over when, in 1912, he published The Nummulosphere, a monumental work that more or less postulates that the entire Earth is made of nummulites. Given enough time, and access to the Hubble Telescope, Kirkpatrick would probably have extended his thesis farther into the cosmos.

So does Kirkpatrick take away the coveted "Master of Self-Delusion" prize? Not even close! Step forward, one Lewis A. Manson. His masterwork, The Birth of the Moon (1978), published by an apparently reputable university press, displayed powers of misinterpretation so great as to leave us breathless with admiration. Manson was clearly a man who knew his own mind, and was not about to be diverted by inconvenient details such as mainstream scientific thought. Whilst also reinventing most of astronomy and atomic physics, his refreshing take on geology included a new era, the Diastrophic.

This era lasted but 96 hours, during which time a passing star dragged off enough crust to form the moon, opening faults into which all sea life disappeared, to be converted to oil 60 miles down. When these chasms slammed shut, huge quantities of sand spurted out, together with the petrified remains of molluscs' fleshy parts (bits of flint to you and me). Manson's lavish illustrations also indentify a fibrous gypsum specimen as a piece of coconut "with the fibres perfectly preserved" and a copper ore concretion as a petrified frog (the green colour was a dead giveaway). Oh, and we almost forgot to mention the dessicated hadrosaur head observed on the lunar surface, and that "man, of course, evolved in the Devonian".

So why are we fascinated by this stuff? Is it just because we like to feel superior? Not at all – these books would be among the first we'd rescue from a burning building. The ability to be spectacularly wrong, shrug your shoulders and move on, is one of the joys or working in an imprecise science. We might even admit to a few howlers of our own, although fortunately space considerations do not permit us to go into those right now.

References

Energlyn, Lord (William David Evans). 1973. Through the crust of the Earth. McGraw-Hill.

Kirkpatrick, R. 1912. The Nummulosphere: An Account of the Organic Origin of So-called Igneous Rocks and Abyssal Red Clays. Lamley & Co. 424p.

Manson, L.A. 1978. The Birth of the Moon. Dennis-Landman Publishers. 205p.

Plot, R. 1677. The Natural History of Oxfordshire. 358p.